Discover the world of paediatric vestibular assessment and management from the team at Alder Hey Children’s Hospital, which is revolutionising services in this field.

Dizziness and balance problems generate significant morbidity in children of all age groups. Vestibular disorders are the commonest causes of balance issues in children. These disorders can lead to cognitive, psychological and somatic symptoms influencing the overall development of the child [1].

Evaluating dizziness in children requires experience, knowledge and extensive training in adult vestibular medicine, general and allied paediatric medical disciplines, especially developmental paediatrics and paediatric neurology.

Awareness regarding balance and dizziness in children in the global perspective is low, with only a handful of dedicated paediatric vestibular centres in the world. It is important to recognise that adult vestibular medicine is very different from paediatric vestibular medicine where norms and diagnostic processes cannot be extrapolated.

The vestibular system in children

The cochleovestibular system develops in utero from six weeks and is fully formed at birth. The uterine phase of development is guided by genetically controlled targeted development for synaptic and neural connections that attain function after birth. After birth, development is driven by sensory cues in the environment. Priming of vestibular function proceeds, following a critical temporal period dependent on neurotransmitter expression and regulation of synaptic connections.

Figure 1: Development of vestibular system.

The development of the vestibular system is shown in Figure 1. Key reflexes resolving space up to six months of age are the primitive developmental reflexes [2]. The vestibulo-ocular reflex becomes functional from two months and the vestibulo-spinal reflexes mature in adolescence. Complete central vestibular integration for the final balance percept incorporating the optical system, the proprioceptive system and the cognitive centres with an eventual output to the motor system is attained at 15 years of age [3]. Knowledge about this development is essential to interpret meaningful age-specific vestibular function test battery.

"A key element to managing the paediatric population with vestibular disorders is to understand illness cognition models, which are applicable to both children and their carers"

The vestibular system in children is just not limited to a vestibular sensation; it also maintains posture and muscle tone, produces kinetic contractions to generate ocular stability and is involved in cognitive and spatial discrimination [4].

Epidemiology of balance disorders in children

The epidemiology of dizziness and balance problems in children in a large US study was 5.3% and increased with advancing age, possibly because of better reporting by older children, out of which at least 18% had a significant problem [5]. In children presenting with balance complaints, as many as 35.84% were diagnosed with a vestibular problem, often with accompanying sensorineural hearing loss [4].

Aetiology of balance disorders in children

The aetiology of balance disorders in children is different from those in adults in terms of phenotype and occurrence. The causes are vast and overlap across paediatric medical disciplines. Medically inexplicable conditions, a third of development incoordination disorders and a third of sensorineural hearing losses can be accounted for or accompanied by a central or peripheral vestibular disorder. The causes are given in Table 1. The commonest cause of paediatric dizziness is vestibular migraine and, unlike in adults, viral acute vestibular neuritis, BPPV and Ménière’s disease are rare in children and are usually secondary [4].

Assessment of the vestibular system in children

A comprehensive and detailed diagnostic algorithm is aimed at diagnosing peripheral and central vestibular disorders and a likely aetiology. It also addresses diagnosing a physical or a psychological cause for vestibular decompensation that generates symptoms. Therefore, a vestibular diagnosis is not just limited to the vestibular system alone. An accurate diagnosis leads to a very successful outcome from management and, thus, diagnosis is of paramount importance.

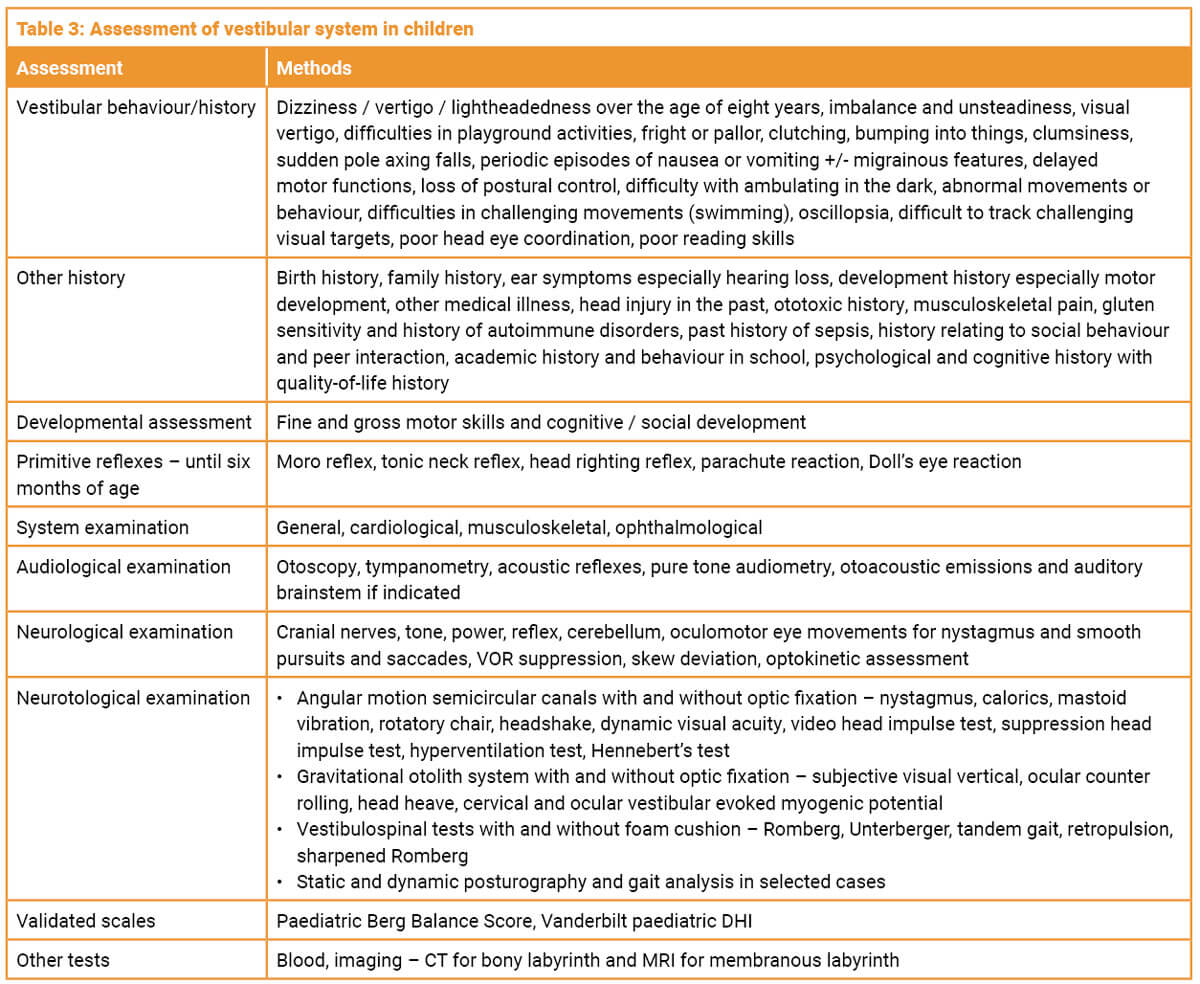

The assessment includes detailed anamnesis, multiple system examination followed by a neurotological examination and laboratory tests. Children up to the age of eight years may not be able to describe a perception of dizziness or imbalance. Eliciting vestibular behaviour from parents is thus pivotal to establish patterns for a diagnosis. In infants under the age of six years, the primitive reflexes are assessed. A clinical examination followed by objective quantification of vestibular function is required in all cases. Choice of tests to glean meaningful information is dependent on the developmental age of the child. Most tests are eminently feasible including in children with autism or attention disorders in a two-tester scenario. Removal of optic fixation and magnification of eye movements is recommended. A full audiological assessment, imaging studies and blood tests are required for determining pathology. An age-determined selection of tests is given in Table 2 and the full battery in Table 3.

Vestibular infant screening

Ghent in Flanders, Belgium, is the first centre in the world to successfully implement vestibular infant screening with cervical evoked myogenic potential test from six months onwards in children with sensorineural hearing loss. Alder Hey in the UK is starting a similar programme with the cVEMP, the remote camera video head impulse test and assessment of primitive reflexes. The objective is to intervene early in vestibular disorder. This is a new field and evidence is awaited.

Management of paediatric vestibular disorders Following diagnosis, treatment is dictated by the aetiology, the level of intrusion in the child’s life and is holistic and multidisciplinary involving, in addition to clinicians, parents / carers and the school. These include sensory integration strategies, psychological intervention when appropriate, correction of visual problems and music therapy, and involvement of multidisciplinary specialists as dictated by the diagnosis.

A key element to managing the paediatric population with vestibular disorders is to understand illness cognition models, which are applicable to both children and their carers. A concrete diagnosis achieves cognitive closure and leads to a sense of wellbeing and, more importantly, reconciliation and self-directed coping strategies built around lifestyle. This leads to a significant improvement in quality of life. Lifestyle changes for specific conditions like vestibular migraine and endolymphatic hydrops with diet and hydration are recommended. Situational counselling regarding activities that involve significant vestibular engagement is important, and adequate physical activity should be encouraged. Treatment of the primary cause, whether through surgery, pharmacological management, or particle repositioning manoeuvres, should be pursued when appropriate. Conditions such as space-occupying lesions, semicircular canal dehiscence, vestibular migraine, paroxysmia, endolymphatic hydrops, and BPPV may require these treatments. Similarly, any cause of decompensation must be managed properly.

"Vestibular rehabilitation should not be a blanket treatment option for all children presenting with dizziness and balance problems"

Vestibular rehabilitation should not be a blanket treatment option for all children presenting with dizziness and balance problems. The decision depends on the quality of lives of children and the proper quantification of a vestibular weakness and evidence of decompensation. If no weakness can be quantified, then it depends on the presence of a vestibular history (central or peripheral) and vestibular behaviour affecting QOL. When selected correctly, it remains the best option to treat a vestibular syndrome in a child as it promotes natural central compensation [4]. It should be instituted early after diagnosis and needs to be customised according to individual needs. The outcome that is measured by vestibular function tests and pre- and post-rehabilitation validated psychometric questionnaires is very favourable and rewarding. It has limited effectiveness in active and irritant vestibular lesions like vestibular migraine, Ménière’s syndrome and vestibular paroxysmia.

Conclusions

Diagnosing balance disorders in children is challenging as they are so complex. These are often interpreted as neurological problems and journey times can be long. Intervention makes a significant difference in many children’s and parents’ lives, so recognition / diagnosis is crucial. It is holistic, multidisciplinary and very rewarding, with favourable outcomes from management.

References

1. Wiener-Vacher SR, Hamilton DA, Wiener SI. Vestibular activity and cognitive development in children: perspectives. Front Integr Neurosci 2013;7:92.

2. Matuszkiewicz M, T Gałkowski. Developmental Language Disorder and Uninhibited Primitive Reflexes in Young Children. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2021;64(3):935–48.

3. Božanić Urbančič N, Battelino S, Vozel D. Appropriate Vestibular Stimulation in Children and Adolescents-A Prerequisite for Normal Cognitive, Motor Development and Bodily Homeostasis-A Review. Children (Basel) 2023;11(1):2.

4. Dasgupta S, Mandala M, Salerni L, et al. Dizziness and Balance Problems in Children. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2020;22:8.

5. Lee JD, Kim CH, Hong SM, et al. Prevalence of vestibular and balance disorders in children and adolescents according to age: a multi-center study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2017;94:36–9.

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.