The issue of ambient music in the operating theatre is frequently controversial and has been known to cause ‘Bluetooth wars’, as different team members vie for control of the speakers. Our own Chris Potter gives his personal slant on this vexed topic.

Können Tränen meiner Wangen Nichts erlangen,

O, so nehmt mein Herz hinein!

If the tears on my cheeks can Achieve nothing,

O then take my heart!

JS Bach - St Matthew Passion

Something kinda, ooooh

Jumping on my toot, toot

Something ‘side of me

Wants some part of you, oooh

Something kinda, ooooh

Bumping in the back room

Something ‘side of me

Wanting what you do, ooooh

Girls Aloud - Something Kinda Ooh

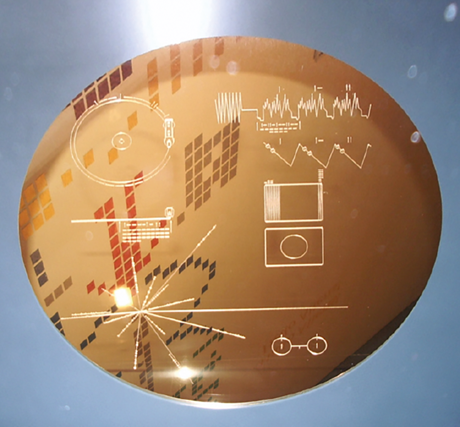

On 25 August 2012, for the first time in history, a man-made object left our solar system for interstellar space. The Voyager 1 probe, launched in 1977, carried on board a state-of-the-art gramophone and Golden Record (Figure 1) designed to dazzle any alien race with the glory of human creativity. A handpicked committee of NASA’s finest minds and cultural bigwigs had deliberated for more than a year over the contents, almost coming to blows on several occasions.

Figure 1. The Voyager Golden Record is currently further from Earth than any other artificial object.

Eventually, in exasperation, it was suggested that we just fill the record with a couple of hours of Bach, whereupon Carl Sagan dismissed the idea on the basis that any aliens would assume we were showing off.

The record was not an unqualified success given that the opening greeting was spoken by the United Nations Secretary General at the time, Kurt Waldheim; now notorious for his war record as an enthusiastic Nazi anti-Semite who developed convenient amnesia in later life over the numerous war crimes committed within his line of sight.

“One of the few closely-guarded perks of being a consultant surgeon is the despotic control of all music in the theatre suite.”

EMI, in a glorious piece of short-sighted spite, refused permission for inclusion of the Beatles ’Here Comes the Sun’ for copyright reasons. In 40,000 years the probe is due to reach the star system AC +79 3888, whereupon we may expect the royalties to start flooding in. The only reason for mentioning the above is to give you an idea of the amount of soul-searching that has gone into my own personal theatre ‘playlist’.

Having ascended the greasy pole of surgical training over the best part of two decades, and endured untold hours of aural torture at the hands of tone-deaf tasteless philistines (yes I’m talking about you, Mr Corbridge, with your inexplicable fondness for Dean Martin) I finally have my own exquisitely manicured hand at the wheel and can inflict my personal eclectic repertoire on all and sundry. After all, like the old feudal baron and his ‘droit de seigneur’, one of the few closely-guarded perks of being a consultant surgeon is the despotic control of all music in the theatre suite.

There may be a current vogue for idle blather about horizontal hierarchies and teamwork from those ‘human factor’ zealots, but when it comes to music this all vanishes under the iron fist of the surgical MC. Now the science of dendrochronology supposedly enables one to accurately date an ancient wooden artefact from the pattern of its tree-rings, and I would propose that it is similarly possible to ascertain the vintage of a surgeon from the contents of their theatre playlist. My own personal popular musical tastes were sealed (like Han Solo in so much carbonite) sometime in the mid-90s, and it doesn’t take a PhD in musicology to note my fondness for shoe-gazing, early BritPop and a touch of Madchester. This is somewhat unfortunate for my long-suffering trainees suckled on the pap of Gaga, Rihanna and Katy Perry, but spare them no pity and shudder for their poor trainees in a couple of decades’ time.

The great pioneer of music in the operating theatre was Evan O’Neill Kane, who noticed the anxiety of his awake patients was not reduced by his assistants’ feeble conversational gambits. In 1914 he started using a phonograph to ‘soothe the savage beast’, as it were. Kane seems to have been something of a rum cove, gaining fame at the age of 60 for carrying out his own local anaesthetic appendicectomy (Figure 2) and hernia repair (at 70) and developed the bizarre habit of tattooing neonates and their mothers with discrete symbols to prevent misidentification. Some of his innovations caught on more than others, but the presence of music in theatre has stood the test of time and, until recently, seemed a permanent fixture.

Figure 2. Dr Evan O’Neill Kane removing his own appendix for reasons best known to himself.

However, a recent paper in the Journal of Advanced Nursing [1] has called into question the safety of our beloved theatre tunes. The original research, heavily promoted by press releases, is described as an ethnographic observational study of teamwork in operating theatres. This appears merely to consist of videotaping 20 procedures and counting how often the scrub nurse ignores the surgeon as he asks for the ‘damn Cottles for pity’s sake’. In my personal practice, indifference on the part of the scrub team to my immediate needs seems to be worn as some sort of badge of distinction, with the senior sister almost completely oblivious to my quite reasonable requests for assistance. She clearly has very firmly held beliefs about the range of instruments I ought to be using and my personal powers of persuasion to overcome this are woefully inadequate. Anyway, the major finding of the study, trumpeted widely throughout the popular press, was that communications were five times more likely to go unheeded in the presence of music.

“The great pioneer of music in the operating theatre was Evan O’Neill Kane, who noticed the anxiety of his awake patients was not reduced by his assistants’ feeble conversational gambits.”

Before jumping to premature conclusions, we must remember a famous study showing that surgical task performance in the laboratory is actually enhanced and autonomic stress responses reduced by the presence of surgeon-selected music [2]. Experimenter-selected music unsurprisingly showed no effect. This of course fits with universal human experience - hominids have used music to provide a soothing atmosphere of calm and improve performance since time immemorial, hence my penchant for the Goldberg Variations during complicated ESS. It’s not purely to irritate the scrub staff and torment the chap with the two syringes (the clear and the white) who tries to keep the patient marginally less alert than my registrar.

The Journal of Advanced Nursing paper concluded that there is “an urgent need to address music at practical and policy level” [1]. It’s difficult to argue with such reasoning as we all know that healthcare issues are generally best addressed by managerial dictats based on risibly flimsy evidence bases. If we lose music in theatre we also lose a valuable method of subtle communication across the blood-brain barrier - Elvis Costello’s Almost Blue and Leona Lewis’s Keep bleeding, keep, keep bleeding have proven priceless in rousing our anaesthetic colleagues from their Sudoku-inflicted slumber.

References

1. Weldon SM, Korkiakangas T, Bezemer J, et al. Music and communication in the operating theatre. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2015;71(12):2763-74.

2. Allen K, Blascovich J. Effects of music on cardiovascular reactivity among surgeons. JAMA 1994;272:882–4.